(In the Herald-Citizen 5/1/20)

This month begins the 250th anniversary of the start of Danvers’ role in the American Revolution. While the 250th anniversary of the 1776 Declaration of Independence is not until 2026, the people of Danvers played important roles during the years leading up to the Revolution: protesting injustices, briefly (and unhappily) hosting the headquarters of the British Army in North America, declaring themselves independent from the king long before the Declaration of Independence, and answering the call to fight the British when they marched on Lexington – to say nothing of other events that occurred during and after the War for Independence.

May 1770 – 250 years ago this month – was an important turning point for Danvers because the town meeting passed a resolution against the importation of tea and began shaming those who continued to support His Majesty’s Government instead of local elected authority. As Parliament leveled more and more taxes on the colony without the agreement of the Massachusetts legislature, and without any colonial representation in Parliament, the people of Massachusetts protested against this unfair taxation without representation.

During the 1760s, patriotic merchants in Boston signed agreements not to import any taxed goods from Britain. The resulting economic harm forced Parliament to withdraw the taxes on many items – but not the tax on tea. On May 28, 1770 the men of Danvers gathered for a town meeting at the First Church to discuss the issue. Unanimously, they voted to boycott any merchant who imported British goods and agreed “That we will not drink any foreign tea ourselves, and use our best endeavors to prevent our families and those connected with them, from the use thereof” until the tax was repealed.

To emphasize their determination, a committee was elected to bring a copy of this town meeting resolution to residents and have every head of household sign it. If someone refused, the town meeting voted that “he shall be looked upon as an enemy to the liberties of the people, and shall have their name registered in the town [record] book.” Additionally, these resolutions were published in the local newspaper, the Essex Gazette, so that all were warned.

Because of this threatened humiliation and damage to one’s reputation, there seems to be only one recorded instance of someone publicly refusing to sign: A man named Isaac Wilson who lived in the southern part of Danvers, now Peabody. Due to his opposition, he was taunted about being a “Tory” (one who remained loyal to the king). Though, as the Revolution approached, a few other families in Danvers aligned themselves with the Tory side and remained loyal to the king, leaving town when the war began.

In addition to this example of outright opposition, some of the households that publicly signed the ban privately violated it. Tea was often bought in bulk, so why shouldn’t tea that a family had purchased before the ban be consumed? The tax had already been paid, so Britain received no further gain whether they drank it or dumped it out. Nineteenth-century historians note several instances of families acting this way, especially instances where wives decided to consume the tea they already had on hand with or without the knowledge of their husbands.

The most famous story of thwarting the tea ban in Danvers – though apparently kept secret at the time to not tarnish the family’s patriot reputation – was Sarah Page’s covert tea party on the roof of the Page House. This legend was enshrined in the poem “The Gambrel Roof” by Beverly writer Lucy Larcom (1824-1893), who knew Sarah Page’s granddaughter. Though potentially based on true events, Larcom’s poem is a romanticized version of the story that was published in 1874 during the lead up to the US Centennial in 1876.

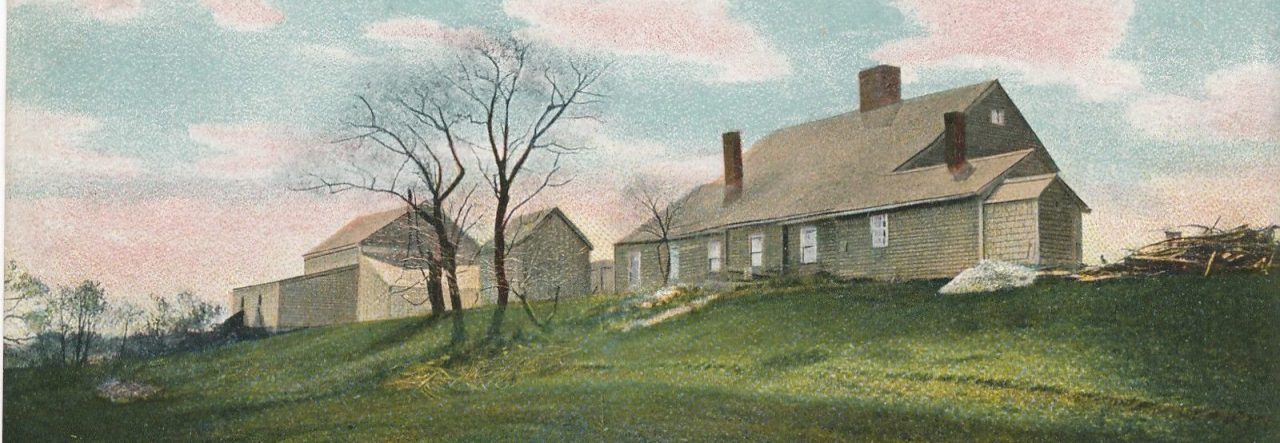

Sarah Page’s husband Capt. Jeremiah Page was a Danvers militia officer and an ardent patriot who later fought in the Revolution. He agreed with the tea ban, and Larcom’s poem supposes that he said “none shall drink tea in my house.” One evening when her husband was out, Sarah Page is said to have invited several women from the neighborhood up to the porch atop the Page House’s gambrel roof, not doing so until sunset so that they would not be noticed. Larcom quotes Page as telling her friends, “Upon a house is not within it,” thereby finding a loophole around her husband’s directive.

The Page House remained in the family for two more generations, and was originally on Elm Street where “Instant Shoe Repair” and “Nine Elm” are today. Sarah Page’s daughter in-law Mary Page died in 1876 and her will put the property into a trust with the stipulation that once there were no longer any Page descendants to live there, the historic house was to be torn down. After Mary Page’s daughter Anne Lemist Page died in 1913, the trustee planned to demolish it according to her wishes.

Losing a house in which two local figures prominent during the Revolution lived would have been a tragedy, and the still relatively new Danvers Historical Society sued to oppose the will. The Essex County Probate Court sided with the Historical Society, and allowed the organization to purchase the house from the estate to preserve it, which it did in August 1914. The Page House was later moved a short distance around the corner to Page Street where it stands as the Society’s office and book shop, still with its gambrel roof and porch atop it.

——————————————————————————————————————————–

Sources:

Addison, Daniel Dulany. Lucy Larcom: Life, Letters, and Diary. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1895.

Gill, Eliza M. “Distinguished Guests and Residents of Medford.” The Medford Historical Register 16, no. 1 (January 1913): 1–14.

Larcom, Lucy. The Poetical Works of Lucy Larcom. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1884.

“Newspaper Items Relating to Danvers.” In The Historical Collections of the Danvers Historical Society, 1:61–64. Danvers, Mass.: Danvers Historical Society, 1913.

Nichols, Andrew. “The Original Lot of Col. Jeremiah Page.” In The Historical Collections of the Danvers Historical Society, 3:101–9. Danvers, Mass.: Danvers Historical Society, 1915.

Tapley, Harriet S. Chronicles of Danvers (Old Salem Village), Massachusetts, 1632-1923. Danvers, Mass.: The Danvers Historical Society, 1923.