On hot summer days, we take for granted the treat of having a crisp cold drink with ice cubes in it, not to mention the ability to refrigerate and freeze food. In the 19th and early 20th centuries the advent of the ice industry made this refrigeration possible and radically changed the lifestyles of everyday people. Danvers was the site of a booming local ice industry during these years, and a group of Danvers entrepreneurs capitalized on this new industry by establishing an international ice trade.

The Mill Pond, known for centuries as Putnam’s Pond, was the center of the local ice trade. The pond was originally a meadow that was flooded when Beaver Brook was dammed. The dam today is under Sylvan Street at one end of the pond, and for over 250 years the Putnam Family operated a sawmill powered by the flowing water. Although not the original intention, the pond became a perfect location to harvest ice.

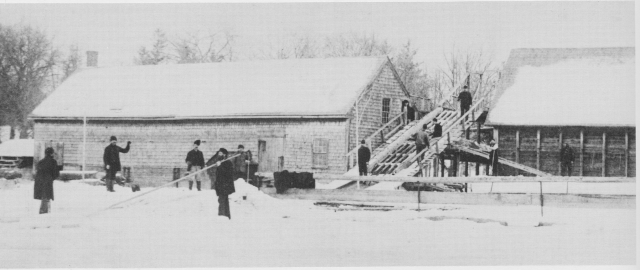

(Putnam saw mill in the foreground, with the ice houses in the background. Road at bottom right is Sylvan St. Courtesy of the Danvers Archival Center. Republished from Zollo, Trask, and Reedy, As the Century Turned).

The Otis F. Putnam Ice Company took advantage of this opportunity. Boards would be added to the dam to raise the water level in the pond at the start of winter. Over the course of the cold months, the pond would freeze at least 10 inches deep. Then, the snow would be shoveled off, and metal tools were used to cut a grid pattern 3 inches deep into the ice. A horse then pulled a sharp tool down the pre-cut grid lines, separating the squares into blocks of ice.

(Workers from the Otis F. Putnam Ice Company harvesting ice from the Mill Pond in 1900. Courtesy of the Danvers Archival Center. Republished from Zollo, Trask, and Reedy, As the Century Turned).

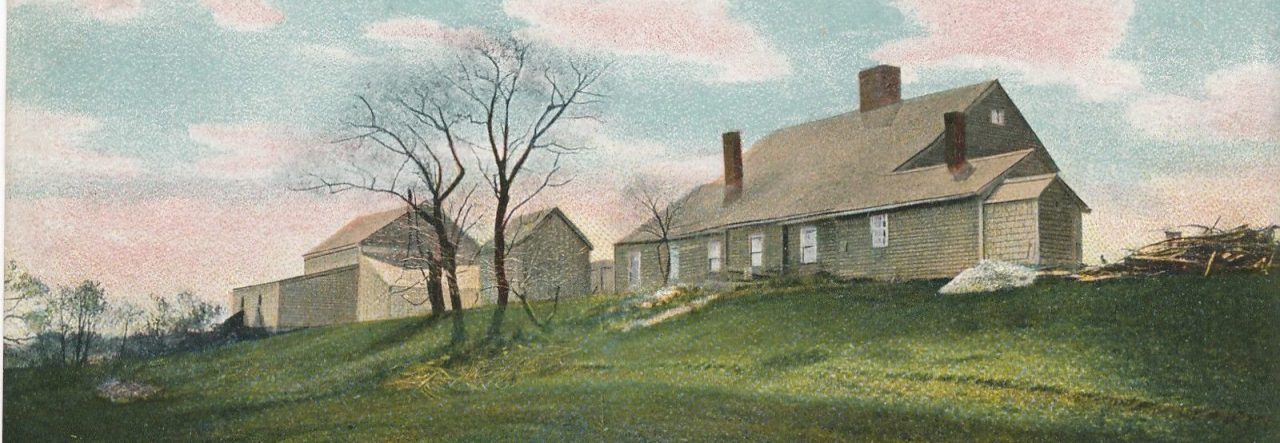

These blocks were then floated over to the Sylvan Street dam and through the narrow opening to an ice house that sat where the Walnut Grove Cemetery is now. The blocks were packed in sawdust or hay, which insulated them and prevented melting. About 6,000 tons of ice were harvested each year from the pond, and some years two rounds of ice could be harvested if the weather stayed cold long enough.

(Another view of Putnam’s ice house, located at the present-day site of Walnut Grove Cemetery. Courtesy of the Danvers Archival Center. Republished from Zollo, Trask, and Reedy, As the Century Turned).

During the warmer months, the iceman traveled around town in an insulated wagon delivering ice to the kitchens of Danvers to keep food cold in the iceboxes. This Mill Pond ice was used primarily for refrigeration, not as ice cubes in drinks. One reason is that ice was too expensive to use frivolously, but also the quality of the water was in question. Beginning in 1901 the town consulted with the state board of health about pollution in the pond from nearby industries, and the state restricted the consumption of ice to only the top most layers of the pond.

(The Otis F. Putnam Ice Company delivery wagon at the turn of the century. Courtesy of the Danvers Archival Center. Republished from Zollo, Trask, and Reedy, As the Century Turned).

While the Putnam Ice Company served local customers, another group of Danversites plied their talents at the international ice trade. In 1845 a fire swept through downtown Danvers, which destroyed the house and shop of shoe manufacturer Joshua Silvester. He then went to England to establish a shoe factory, but while there discovered the great demand for ice in the large cities of Britain. When he returned to Danvers in 1846, he suggested to several of his friends that they should enter the ice business. Silvester himself was unable to be a partner after the losses he suffered in the fire, so his friends formed a stock company led by Henry T. Ropes.

The Danvers businessmen bought out a Salem company owned by Charles B. Lander that was doing a brisk trade sending ice from Wenham Lake to icehouses in Liverpool, England. The ice was cut and collected at Wenham Lake, and shipped by rail to Boston where it was packed in sawdust for the voyage to England. One of the builders of the rail spur from Wenham Lake to the railroad mainline along Locust St. in Danvers was Grenville Dodge, the Danvers native who later oversaw the building of the eastern half of the Transcontinental Railroad.

The business was slow to make returns for the Danvers men, but Ropes persevered and became very wealthy once the business took off. From 1860 to 1880 Wenham Lake produced as much as 30,000 tons of ice annually, but this was not enough to meet demand. As the business expanded in Britain, the Danvers company needed to ship more ice than could be supplied locally so it expanded operations into Norway. Although it may seem hard to believe that shipping ice across the ocean in cargo ships was cost-effective, it was actually far cheaper to send this natural ice halfway around the world than it was to make “artificial ice” with prohibitively expensive machines.

The Danvers company marketed its ice not just to ordinary consumers for refrigeration, but also to the wealthy for use as ice cubes in drinks. The early shipments of ice from New England changed British society. One other early American ice company also imported American bar tenders to show the London elite how to enjoy cocktails with ice in them.

On April 2, 1892, a Liverpool newspaper ran an article with the headline “Ice is King” which described the Danvers company’s enormous success over the previous decades. The article also noted that the company had presented a gift of ice to Queen Victoria and the Royal Family, who were quite pleased with this new luxury.

Both locally and internationally the ice industry continued until the age of electrical refrigeration. The ice houses along the Mill Pond in Danvers burned down in 1935, thereby ending the local harvesting of ice. But, the ice at the Mill Pond continued to be used by children who skated on it for decades, until it no longer froze through solidly enough to be safe.

———————————————————————————————————————————–

Sources:

Commonwealth of Massachusetts. Annual Report of the State Board of Health of Massachusetts. Vol. 41. Boston: Wright and Potter Printing Co., 1910.

“Natural Ice.” Cold Storage and Ice Trade Journal, March 1906.

Putnam, A.P. “Wenham Lake and the Ice Trade.” Ice and Regrigeration, July 1892.

———. “Wenham Lake and the Ice Trade.” Ice and Regrigeration, August 1892.

———. “Wenham Lake and the Ice Trade.” Ice and Regrigeration, September 1892.

Tapley, Harriet S. Chronicles of Danvers (Old Salem Village), Massachusetts, 1632-1923. Danvers, Mass.: The Danvers Historical Society, 1923.

Zollo, Richard P., Richard B. Trask, and Joan M. Reedy. As the Century Turned: Photographic Glimpses of Danvers, Massachusetts. Danvers, Mass.: Danvers Historical Society, 1989.

Thanks Dan for your great post. As my name suggests, this article is about my ancestor’s ice business. Otis Flint Putnam, my great great grandfather, started the ice business which was continued by his son, my great grandfather, George Osgood Putnam.

Enjoy your posts of Danvers history. Never lived there, but my father was born and raised there.

LikeLike

I’m happy you enjoy them! That’s cool that it was your family who ran the ice business!

LikeLike

Pingback: Turn-Of-The-Century Danvers – Specters of Salem Village