(In the Danvers Herald, 10/4/19)

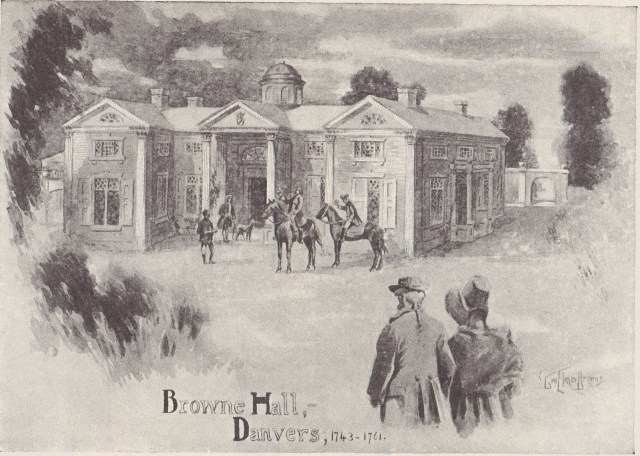

(Image of Browne Hall reprinted in Harriet S. Tapley, Chronicles of Danvers (Old Salem Village), Massachusetts, 1632-1923 (Danvers, Mass.: The Danvers Historical Society, 1923).

In 1740 a large mansion was built atop Leach’s Hill, a home whose construction was deemed a folly and altered the name of the hill itself. Today featuring the large water tanks towering above Route 128, the hill lost its former glory due to one of the worst natural disasters in New England history.

In those days, from the summit of the hill one could see Mt. Monadnock in New Hampshire, the Blue Hills in Milton, and the hills of Chelmsford. Today the Boston skyline remains visible on the southern horizon, as is the ocean to the east, and the old Danvers State Hospital perched atop Hathorne Hill to the west. Folly Hill is visible from all across the north shore, and attracted local explorers and wanderers such as Nathaniel Hawthorne, who as a young man in the early 1800s explored the hilltop and ruins of “Browne’s Folly.”

(Looking south from Folly Hill, September 2019. Danversport Yacht Club and Sandy Beach in the foreground, and the Boston skyline in the background. Author’s photo.)

William Browne, a wealthy Salem merchant, representative in the Massachusetts legislature, and member of the Governor’s Council, purchased the hill for the location of a fine country estate. In 1740 he built “Browne Hall,” an 80-foot long mansion that consisted of two wings connected by a central entrance hall. The house was extravagantly furnished and built in a neoclassical style, with columns around the main doors and the floors painted to look like a mosaic.

One visitor noted that the entrance hall had an oval gallery with a fine railing above the ballroom, and a large dome for the roof. The mansion had four main entrances – one facing north, east, south, and west – and if all of the doors were propped open, one could stand in the center under the dome and see outside from all four directions. An opulent palace for a wealthy man, this house on the summit of the hill was visible for miles – but its precarious location atop the hill was its downfall.

At 4:30am on November 18, 1755, people across Massachusetts and the Atlantic coast suddenly awoke. The ground rumbled for four and a half minutes, walls shook, and chimneys crumbled as a powerful earthquake struck the area. The quake’s epicenter was off Cape Ann, but its effects were felt as far away as Nova Scotia and South Carolina. Clocks stopped in Boston and more than 1,500 chimneys crumbled, while in New Haven the ground rose and fell like waves on the ocean. Out on the actual sea, sailors 200 miles from the coast felt the rumbling and feared that their ship had run aground. The earthquake was the strongest ever felt in Massachusetts – likely between a 6.0 and 6.3 if measured on the modern Richter scale – and may have caused a tsunami as far away as the Caribbean.

Once the tremors ceased, the inside of Browne Hall was littered with broken glass and it was feared that part of the structure was compromised. Browne no longer considered the home safe to live in due to the damage, which was exacerbated by the house’s location on the peak of the hill. Abandoning this prominent yet precarious location, Browne moved part of the mansion to the corner of Liberty and Conant Streets in Danvers. William Browne passed away eight years after the earthquake and was buried in Salem’s Charter St. Cemetery, leaving the remnants of his once-glorious estate in Danvers to the next generation.

The remaining part of the house, now at its much lower location, was inherited by Browne’s nephew and heir. But, his nephew was a Loyalist during the Revolution and so all of his property was confiscated, including the remnants of Browne Hall. Browne’s nephew returned to England during the Revolution and later became the Royal Governor of Bermuda. The part of the house at the end of Liberty Street was left abandoned, with all of the home’s furnishings still within.

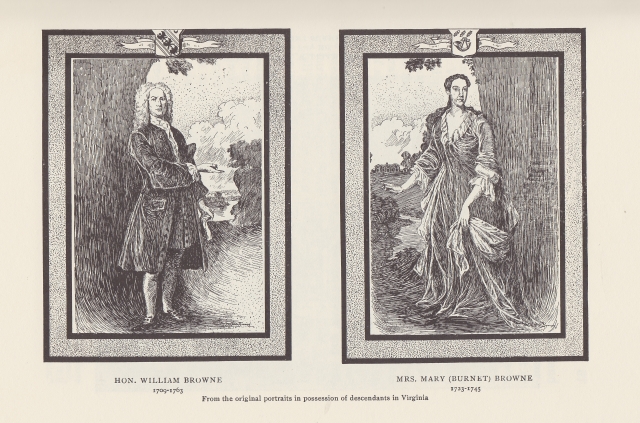

This unkempt building became known as a haunted house, and local children dared one another to enter. Nathaniel Hawthorne recounts the story of several boys hesitantly exploring the deserted mansion, believed to be the home of some evil spirit. On one adventure, they opened a door only to have specters of the home’s former owners lurch out of the closet at them as they turned tail and fled. These images were later discovered to be merely Browne family portraits tumbling off a shelf, rather than ghosts of the home’s former inhabitants.

(Two of the Browne family portraits that were kept in Brown Hall. Reprinted in Ezra D. Hines, “Brown Hill and Some History Connected With It,” Essex Institute Historical Collections 32 (1896): 201–36).

The remnants of Browne Hall were later sold off in sections. The central hall became part of the Danvers Hotel, which was located where the savings bank building is now at one corner of Danvers Square. It was later relocated yet again across the Square, but it burned in a large fire that destroyed the whole area in 1845.

After the house was removed, the hill – by now renamed “Folly Hill” due to Browne’s folly of building such a large house at the pinnacle of the hill – remained empty during the following decades. Hawthorne enjoyed taking walks to the open land around Salem, and frequently took a route that led him across the Salem-Beverly Bridge, down Bridge Street and Elliott Street past the hill, and then down Liberty Street back to Salem. He wrote about the green cart path that led to the top of Folly Hill, the overgrown cellar hole of the house, and the marvelous view of the surrounding towns from the summit.

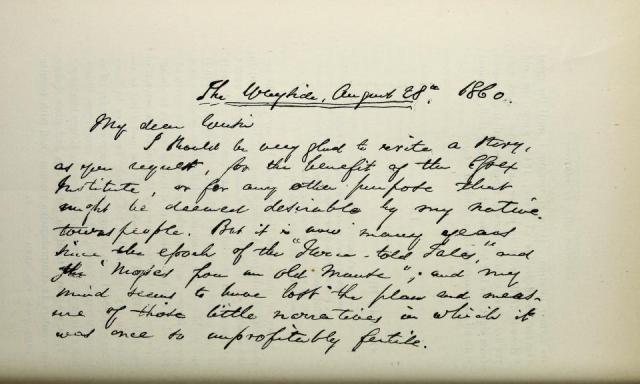

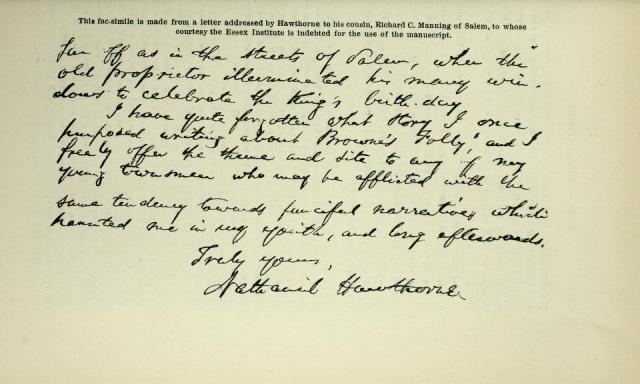

Hawthorne, in a letter to his cousin, described the remains of Browne Hall as a connection to a prior glorious age before the Revolution and the uncertainty that followed. He wrote, “The ancient site of this proud mansion may still be traced upon the summit of the Hill… there I have sometimes sat and tried to rebuild, in my imagination, the stately house, or to fancy what splendid show it must have been even so far off as in the streets of Salem, when the old proprietor illuminated his many windows to celebrate the King’s birthday.”

(Image of part of Hawthorne’s letter describing Folly Hill, reprinted in Ezra D. Hines, “Brown Hill and Some History Connected With It,” Essex Institute Historical Collections 32 (1896): 201–36).

—————————————————————————————————-

Sources

Ebel, John E. “Massachusetts Historical Society: The Cape Ann Earthquake of November 1755.” Massachusetts Historial Society, November 2005. http://www.masshist.org/object-of-the-month/objects/the-cape-ann-earthquake-of-november-1755-2005-11-01.

Hawthorne, Nathaniel. “Browne’s Folly.” In The Complete Works of Nathaniel Hawthorne, 12:131–35. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1878. https://books.google.com/books?id=Dx5EAAAAYAAJ&dq=hawthorne+Browne%27s+folly&source=gbs_navlinks_s.

Hines, Ezra D. “Brown Hill and Some History Connected With It.” Essex Institute Historical Collections 32 (1896): 201–36.

Tapley, Harriet S. Chronicles of Danvers (Old Salem Village), Massachusetts, 1632-1923. Danvers, Mass.: The Danvers Historical Society, 1923.

Very interesting. Didn’t know about the mansion nor the earthquake.

LikeLike